While men still set the rules of a patriarchal power structure in Korean society, it is women who control and dominate the sartorial conversation as it has to do with gender rules, roles, and the nature in which they are performed. Women define the rules of fashion and beauty's semiotic grammar so completely that it is no surprise, at the sartorially serious, extreme end of the spectrum, to see prettified Korean men wearing makeup, feminine colors, and even in this case, white fishnet stockings, and it make a certain kind of sense here. He's not cross dressing, e.g. breaking cisgender role norms. He just looks in place here, i.e. very dressed up for fashion week.

Photographic Flaneurie in Seoul, Or Lamentations over the Stillborn Tradition of Street Photography in Korea

Much as modern sociology has strong generative roots in the conflict of modernity and urbanization that sparked the social reform photojournalism of Jacob Riis or Louis Hine, the entire enterprise of sociology itself finds its origins in the socio-historical moment that produced the flaneur and the sociologist. For example, acclaimed documentary/street photographer Choi Min Shik’s photographs of Korea during the age of rapid development in the 1950s and 1960s are part of a discursive, photographic process that defined the visual grammar and fundaments of “Korea,” both during its formative years and in the popular, nostalgic imaginary of the present. The public conversation about development, gender roles, and even the national sense of self itself has been dominated by a visual imaginary which has been utilised by the state to illustrate its ideological agendas, by popular culture text producers to punctuate their narratives, and has been the realm that photographers worked document lived reality. This is the visual, discursive realm that helps define “Korea” to itself. As a non-Korean street photographer since 2002 and the first “street fashion” photographer and blogger (active since 2006), my intention here is to explore issues of ethics in photographic/ethnographic practice in constructing a specific vision of a "lensed Korea" in a society that has a tense and fractured relationship to national identity, gender, personal rights, and photography as a visual medium in Korean society.

Any French person knows full well what a flâneur is. He is an observer of city life, slightly more focused and sociologically-minded than a rubbernecker, a near-professional observer of the street, of life. He was also the harbinger of modernity, the city and the all-consuming crowd, of the masses and their follies, and quickly moved from the open-air streets to the Arcades (indoor shopping malls) of Paris after this modern, Babylonian contrivance was constructed in the 1860s. The flâneur was, according to philosopher Walter Benjamin, the first modern detective, albeit someone who detected for fun more than profit, and tracked down stories and solved the myriad mysteries of the crowd. The flâneur was a man of means, with the time and resources to not have to work like everyone else, to dedicate oneself to the study of humanity in the city. Of how humanity changes the city. And how humanity is changed by the city. The flâneur , in the original French incarnation, is as old as urbanity, as urbaneness, itself.

Although to even say so flirts with the sin of cliché, put a camera into a flaneur’s hands and you get a street photographer. And Paris famously yielded both Henri Cartier-Bresson and Robert Doisneau, both amongst the word’s most famous street photographers, who were birthed in the cradle of the Metropolis, which was itself -- at least, in Fritz Lang's interpretation, the source of a great deal of ambiguous, uneasy feelings about the nature of modernity and the condition of humanity itself. This tension about the city, identity, and how it all fits into the maw or urbanity continued to be photographed by the likes of Cartier-Bresson and Doisneau in Paris, and Walker Evans, Lee Friedlander, and Robert Frank across America, and strongly continued through the work of Garry Winogrand in New York City., along with many others.

For thinkers and artists with far less fantastical leanings, however, the relatively new technology (and in no time at all, medium) of photography would be a crucial tool in making sense of urbanity as art. Behold, Eugène Atget's photography of Paris in the early years of the 20th century, a revolutionary document of a disappearing, pre-modern way of life that was rapidly giving way to the New and the Modern.

Atget documented the changing landscape of his modernizing home, Paris, and was an important street photographer in that he literally photographed streets, along with people, although the limited technology of the time and its slow shutter speeds made for a very different kind of "street" than we think about today, in the post 35mm-film age. But it is important to remember how revolutionary it was to take a large, heavy camera outside of the studio sitting room and point it at the street, at life in the wild. Atget is famous for being one of the first to do this. And it is no mere coincidence that Paris, the birthplace of modernity itself, was the social laboratory in which this could happen.

Let us move forward to more recent understandings of the "street photographer" as a flaneur with a camera, as a photographer candidly documenting life "wie es eigentlich gewesen," to use the words of Ur-historian Leopold von Ranke. A “street photographer” is someone who produces documents of lived, populated, wild reality with fast lenses, small, 35mm camera bodies, and fast film in natural light. And since it started in Paris, the birthplace of photographed nouveau modernité, it makes sense to simply jump right to Henri Cartier-Bresson, a widely-recognized founding father of the genre.

Cartier-Bresson, another great photographer who developed his style in the petri dish of modern Paris, is usually spoken of in the same breath with his concept of "the decisive moment," which is that singular and special instant in time when all the key elements align in the ideal, optimal way in the frame such that it conveys the full reality the photographer wishes to capture/convey. It is also a key moment of tension between said elements that is transmitted diretly into the mind of the viewer of the photograph. In the years since Cartier-Bresson's heyday in the 1940s-60s, the special quality of that decisive moment, which Cartier-Bresson himself likened to the sport of hunting (and archery, specifically)has become a fetish object for photographers over the years.

Before moving away from the Paris of the flaneur and the photographic flaneurs armed with cameras, it would be remiss of me to omit Robert Doisneau as we talk about great, foundational street photographers.

One of the most iconic images of Paris is the one of two lovers kissing (who were really lovers and whom Doisneau hired as models, a fact which slipped his mind and came to light years later, which led to buzz and rumor that the image had been "faked") -- and indeed, Doisneau's (and many others) images of a Paris that had not yet developed a restrictive legal culture of photographic laws helped construct the image of that city as one of freedom, hedonism, and endless romance, an image that endures to the day.

Similarly, by the time we encounter Garry Winogrand in 1960s New York City, another petri dish of modernity and cosmopolitanism, the liberal legal restrictions on American photography allow for a certain kind of photographic practice that allowed for the kind of pictures that concretized many of our conceptions of NYC culture that still endure today.

[--- continue from here for DoubleDot Magazine piece ---]

Winogrand was a frenetic, nearly crazed shooter who famously quipped that "Photography is not about the thing photographed. It is about how that thing looks photographed" and when asked about missing shots while reloading film, he famously explained, "There are no photographs while I'm reloading."

One reason Winogrand is lionized today has to do with his shoot-first-ask-no-questions-at-all, aggressive, in-your-face-and-her-face-and-his-face, shooting style reminiscent of and congruous with the counterculture, take-no-prisoners artistic Zeitgeist of the times, which could be found in the "gonzo journalism" of Hunter S. Thompson or even the brutally honest photoreportage/cultural critique posed by Robert Frank in The Americans. All of this street and doumentary work was enabled by a photographic legal culture in America that still allows pictures to be taken by and of anyone in a public place. And it was this permissiveness around photographic refulations that allowed these observers of societal change and conflict to do their work that helped define the very mental image have of those places at those times. In the European case in general, and in France specifically, laws surrounding photography have changed drastically, to the point that in most Western European capitals, the street photography that defined them decades ago, of total strangers doing what total strangers do, is illegal today.

A Kim Ki-chan photo from the 1960s was often full of humor, people, and dogs. Development-era days weren't all so bad.

Lee Hyeong-rok documented development-era realities that often flowed in beautiful aesthetic patterns.

This shot, taken by Jeong Beom-tae, demonstrates, all in a single image, the conflicted and complex emotions that come with living in close quarters to a new, neo-colonial master.

Now, we come to the case of South Korea, where the few photographers shooting "street" busied themselves with documenting a post-war, develeopment-era society living in conditions of relative poverty and undergoing massive, rapid social change.

Choi Min-shik, based in Busan, took some of the most iconic and outright critical images of the era, depicting abject poverty and social destitution in a hard-hitting way that outright stings eve to this day This image, converted into full-motion form, defined a major photographic, visual touchstone in the opening long dolly through the International Market in the film of the same name (in Korean as 국제시장), also known in English as Ode to My Father. This film was a tour-de-force as an extremely rose-tinted exercise in reconstructing nostalgic popular memory through and on film. This is one of the most important, historically seminal images in Korean history.

Another Choi Min-shik image, which unabashedly calls out the extreme economic disparities already extant in the early days of the Korean republic.

How the Other Half Lives, Korean-style. A critical gaze worth of that of Jacob Riis.

A classic Kim-Ki-chan image, one of many he committed to film as he went about documenting the golmok, Seoul's back-alleys, where he identified as the formative space for Korean manners, mores, and the backbone of Korean identity itself. I am strongly of the opinion that one of the reasons Kim Ki-chan receives so much popular, positive historical attention relative to many other photographers active during the 60s and 70s is because his depiction and view of Korean development-era life seems to say, quite simply, "Things were kind of tough at times, but overall, they weren't so bad and it gave our people character." They weren't exactly "good times," but they weren't all that bad, either.

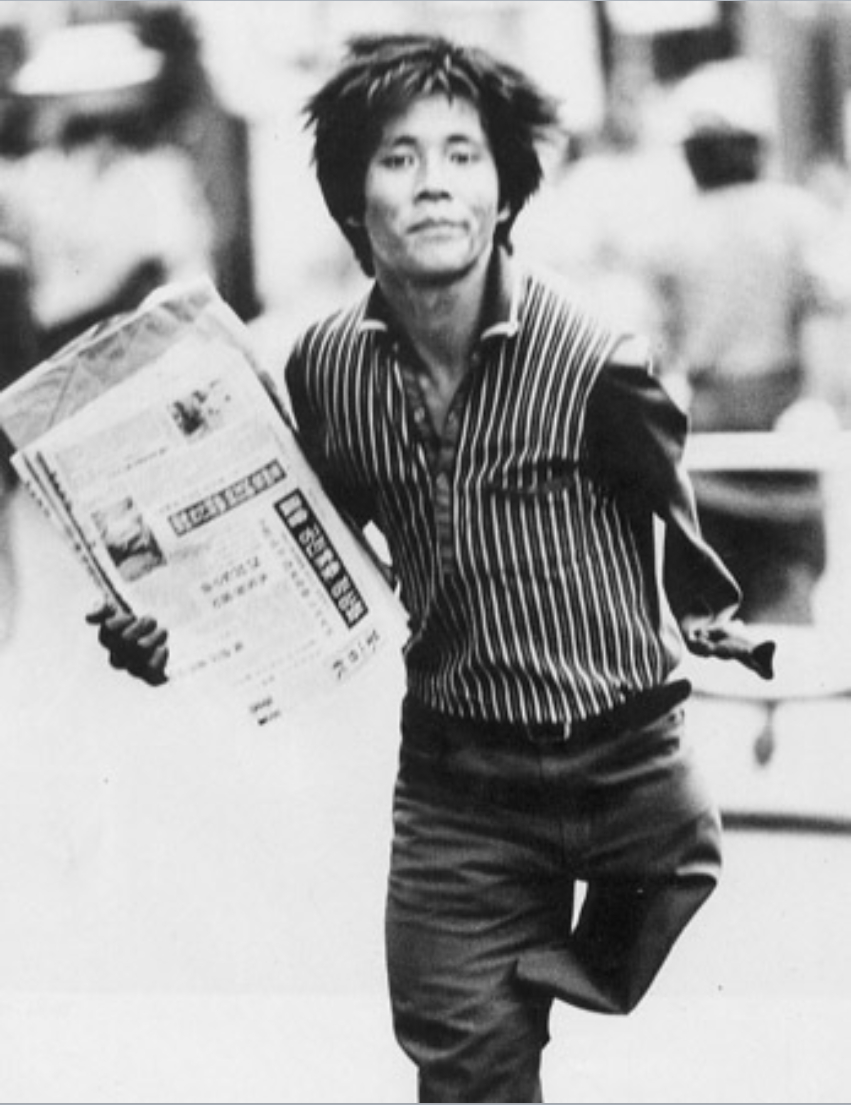

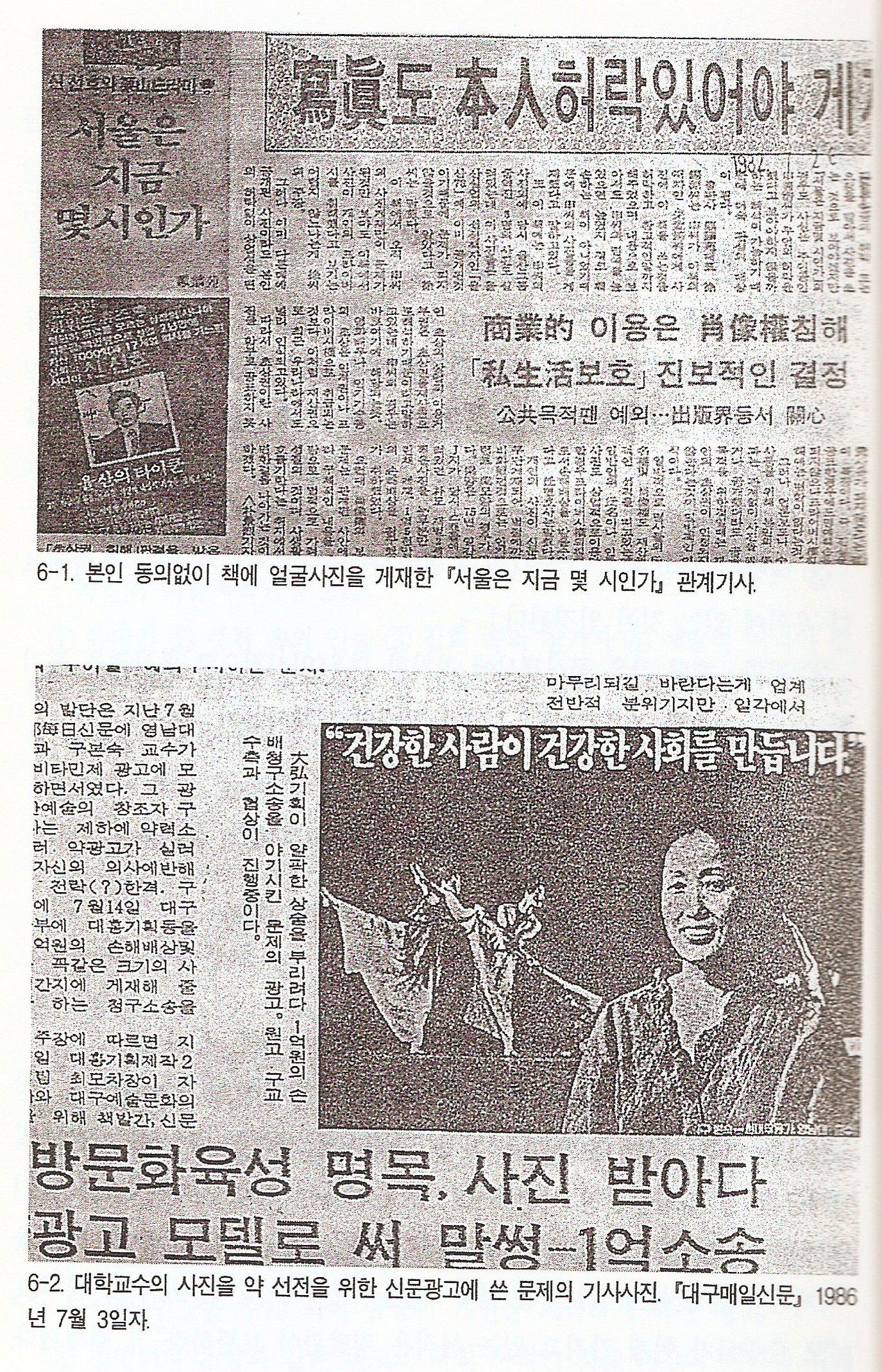

Throughout the development-era year that spanned from the 50s to the 70s, and roughly conincided and were marked by dictatorships and hard times in schools and factories for many people, a period that was also co-terminus witH the Pak Chung Hee regime (1961-1979), photography was largely a pastime of the elite, in a society where many people were much more concerned with where their next meal was coming from than over obtaining and expensive photographic equipment imported from Japan and Germany. That is, until 1980s and 1990s, when a string of high-profile lawsuits over use of prominent social figures' images burst into the public consciousness (in 1982, 1986, 1990, and 1993, generally involving the commercial use of people's images without their explicit permission) and is where I believe the legal term chosang-kweon ("the legal right to control one's facial image") first began being bandied about by laypeople.

Ground zero of when one starts to see the term chosang-kweon start popping up in newspapers is 1982.

A political cartoon illustrating a column on the subject of cameras and the public, written in 1982.

By the time a string of cases regarding the right to publish people's faces in newspapers runs its course throughout the 80s and 90s, the term is firmly entrenched in the public consciousness.

From 한국신문사진론, by 장충종 p. 182.

But before we go any further, we must first go through a short primer on photographic law in South Korea. To begin with, it is important to understand that in a nominally Confucian society, based as it is on clearly-defined and circumscribed social relationships, one's reputation vis a vis one social role and expectations is everything. This is why lawsuits for damage to one's reputation abound in Korean society. Starting a rumor that harms someone else's reputation is clear grounds for a lawsuit, whether or not the information conveyed is actually true.

According to the Korean Constitution, all citizens have a "right to privacy" that extends in particular to the "right to one's facial image." Violation of that right to privacy vis a vis publishing someone's face without their expressed permission (e.g. a couple sharing an ice cream cone in the park) is understood to be a "violation of the right to one's facial image" (초상권침해). The public has a very heightened awareness of this legal concept, in the same way that Americans are overly conversant in psychological terms such as "co-dependency" or "anal retentiveness" or a person being a "paranoid schizophrenic." But it doesn't mean a lot of people actually know what those things really mean, in the original terms of the field they come from.

Same with Koreans, who generally don't speak in such highly-specific jargon. So, the fact that people refer to this very, very specific legal concept should be a give that most people actually don't know what they're talking about. The right to privacy is a generally-protected legal right, just like the "right to one's facial image." However, the right to sue someone for damages for violation of said right is a part of CIVIL LAW (민법), where you can recoup damages for all kinds of violations to your person. There is no aspect of CRIMINAL LAW (형법) linked to the right to privacy or the right to one's facial image that says it is actually illegal to take someone's picture.

If damage results from the "printing or reproduction" of a picture, then you can be sued in a civil law case. And even there, according to further explications of that particular subject in civil law, the person has to demonstrate actual specific damages that resulted from the picture being printed. That's the key point -- not only must the case be argued in a civil case, there has to be more to it than just the fact you took the picture -- actual, concrete damages have to be shown to have specifically resulted from the picture you took.

So, the mere act of taking the picture of a person on the street without their permission is not yet prohibited by any statute of criminal law that I have been aware of for the better part of a decade. The only caveat to this is the new 2013 special law against sexual harassment, which places the photographer in a position of danger based on the mental state of the person complaining. So, written into the law is the idea that if the person feels embarrassment or shame from the picture, and the picture is judged to be of a sexual nature by the officer, you might be brought up on charges of sexual harassment, which could mean a pretty hefty fine and even jail time, in theory, although this almost never happens.

Still, all this has placed a decades-long chill in the air regarding photography on the streets and in public places, to the point that most dabbling in photography don't do street or documentary out of a (mostly mistaken) idea that taking people's pictures without permission is illegal, which it has technically become in some limited situations, although the basis for taking apparently illegal picture is quite legally vague and subjectively defined. But this "chill" is what eventually killed the street photography impulse in many a potential street photographer, although the photographic spirit of certain Korean photographic greats such as Kim Ki Chan and Choi Min Shik could never be cowed. There was great Korean street and documentary photography in megacities such as Seoul and Busan, but the misundertood photo laws created a stifling social atmosphere that have kept generations of even the most camera-crazed Koreans from taking pictures of people and have prevented the creation of long-lasting records of culture and history.

I like to think of myself, as a street (and street fashion) as carrying on the tradition of documenting the Real, of reality, in everyday life, with all its rhythms of life. In that I live in Seoul, Korea and work to document "Korea", I am engaaged in a somewhat different project than many other street shooters in cities across the world over the course of the last couple centuries. But then again, my overarching reason to pick up the camera is largely the same.

Let's begin this sectionwith perfect honesty – upon first glance, Seoul has not always been a pretty nor memorable city. When thinking about the great metropolises of the world – New York, Paris, London, or Rome – certain stock images spring instantly to mind, seemingly out of instinct: the Statue of Liberty, Eiffel Tower, Big Ben, or the Colisseum. Or even without structures that overshadow the very cities they hail from, there are entire cityscapes that are just as deeply burned in the world’s imagination, such as is found in the urban wonderland of neon signs and corporate logos that is downtown Tokyo, the stunning architectural wonders defining the skyline of Shanghai, or the quaint charm of the great seaport city of San Francisco.

Still, I do not mean to be too hard on the city, as I am more than able to acknowledge Seoul’s myriad hidden charms, as well as the fact that there are reasons to fall in love with this peculiar, quirky place. Of course, the taste for Seoul is somewhat acquired, requiring a bit of time to build, just as one might first taste a strange but pleasingly complex wine, or sip an extremely dark beer, or take the first bite of an exotic new food that has an unfamiliar initial punch, but follows up with a pleasant aftertaste that lingers and requires another bite to make sense of what was just tried. And it is in such ways that a new affinity for something is born, out of something that initially seemed strange – or to the eyes and palates of others, downright unpleasant.

No, Korea is not "beautiful" or "dynamic" or "the hub of Asia" simply because Koreans want it to be. Things in Korea are also not "beautiful" simply because they are Korean. They happen to be beautiful things that take place in Korea, in a Korean way. The photos I take are mostly universal. They have cultural contexts, but in the end, they say something essential about the human condition. I leave the lauding of the beauty of the hanbok, celebrating celadon pottery, and extolling the virtues of traditional architecture to the people who think these things may attract tourists. Much more than most Koreans think, most foreigners who are here for any significant length of time are not interested in being tourists – indeed, it is quite difficult to be a perpetual tourist. But this is the state in which most Koreans assume foreigners to be – and in a way – is the most comfortable way to think of us. However, foreigners are as perceptive and pick up on the same social cues and signals that Koreans do; it’s just a matter of getting used to the language and the rhythms of everyday life here, instead of there.

What is even more interesting is how the lived experience of the everyday is becoming more and more the same all over the world, making it easier to comprehend Korean culture and life in the city of Seoul. What is particularly Korean – or Seoulike – about waiting in traffic, falling asleep on the subway, waiting in long lines, or dozing off in front of the television? In a way, the similarities between large world cities such as Seoul, Paris, London, and New York homogenize lifestyles enough to make them superficially similar; what becomes actually somewhat more difficult is finding the culturally particular that says something about Korea, life in Seoul, or the feeling of this city’s fast-moving hustle and bustle, frustrating stoppages, and overall dynamicism. The particular uniqueness of the final mix, as opposed to merely the origins of the constituent elements, is where Korean life is inherently, recognizably Korean.

It's the subtle differences between what is essentially similar that makes "Korea" or "Seoul" all the more comprehensible to us. When we look at Koreans sleeping on the subway, we are not engaging in the "colonial gaze" of the past, when Westerners were looking at Korean peasants in small huts breastfeeding their babies or carrying heavy loads to and fro on their A-frame. We are not gazing at the unfamiliar and alien; we are gazing at an experience with which we are familiar, so familiar that it is the subtle differences that leap out and make the picture interesting. Part of the pleasure of this kind of gaze is recognizing the "us" inside the "them." We smile with wonder as we notice that "they" are not too different from "us." Therein lies the pleasure of recognition in many of my pictures. It is also the reason why both Koreans and non-Koreans can find the common ground to enjoy the same shots.

Korea's charm, its enticing, enchanting power, lies is the sameness of the everyday experience, which has become a globalized state of being, to the extent that we all drive cars, wear apparently "western" clothes, watch the same films, and eat the same franchised, fast, fried foods. But there is a critical difference in their local manifestations where all the fun lies.