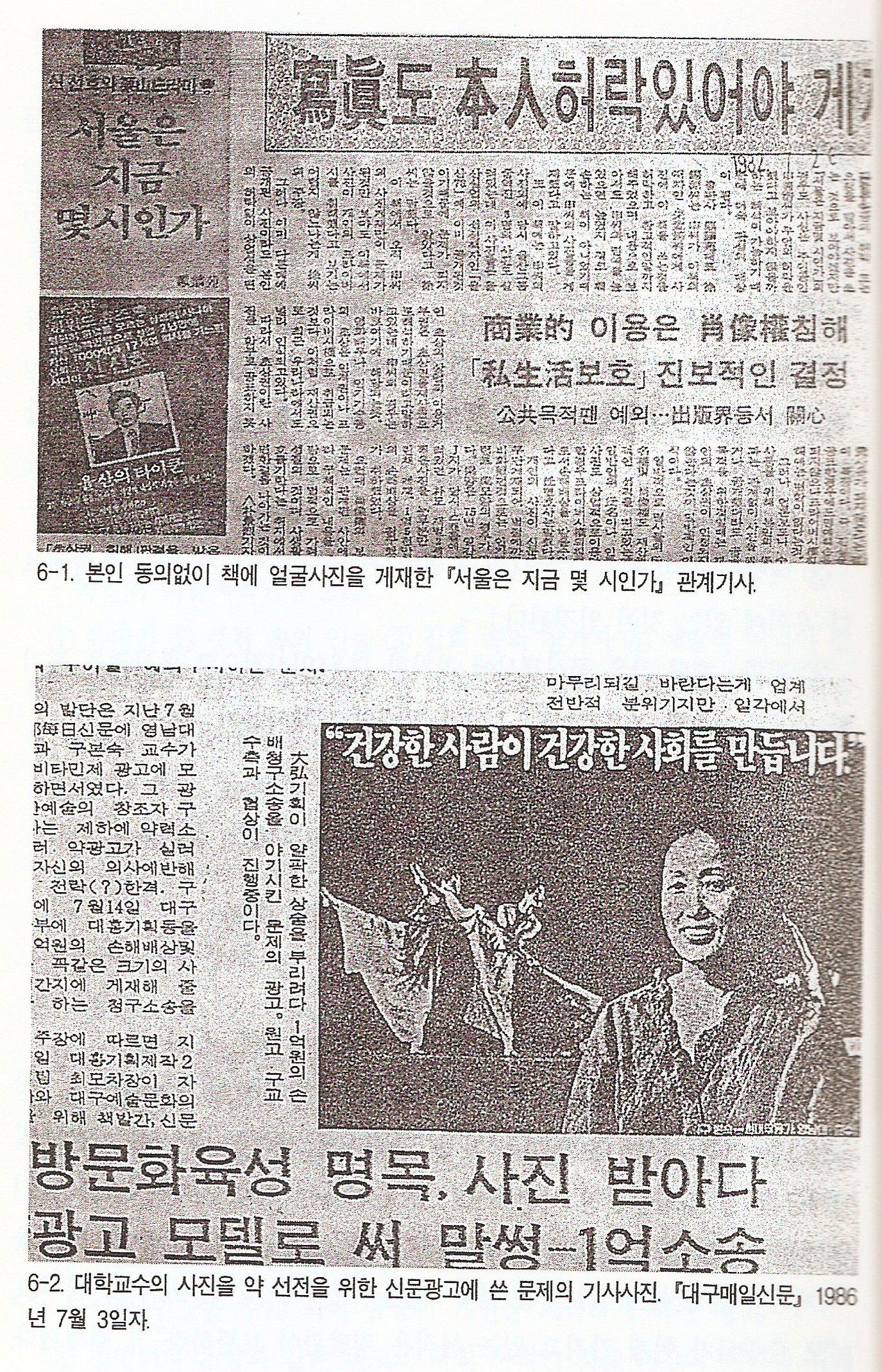

Preface: My Original Title was "Why Street Fashion Is Sociologically Important", but a lot got changed in the process. A translator -- Korea University professor of Sociology Oh Ingyu -- did the Korean.

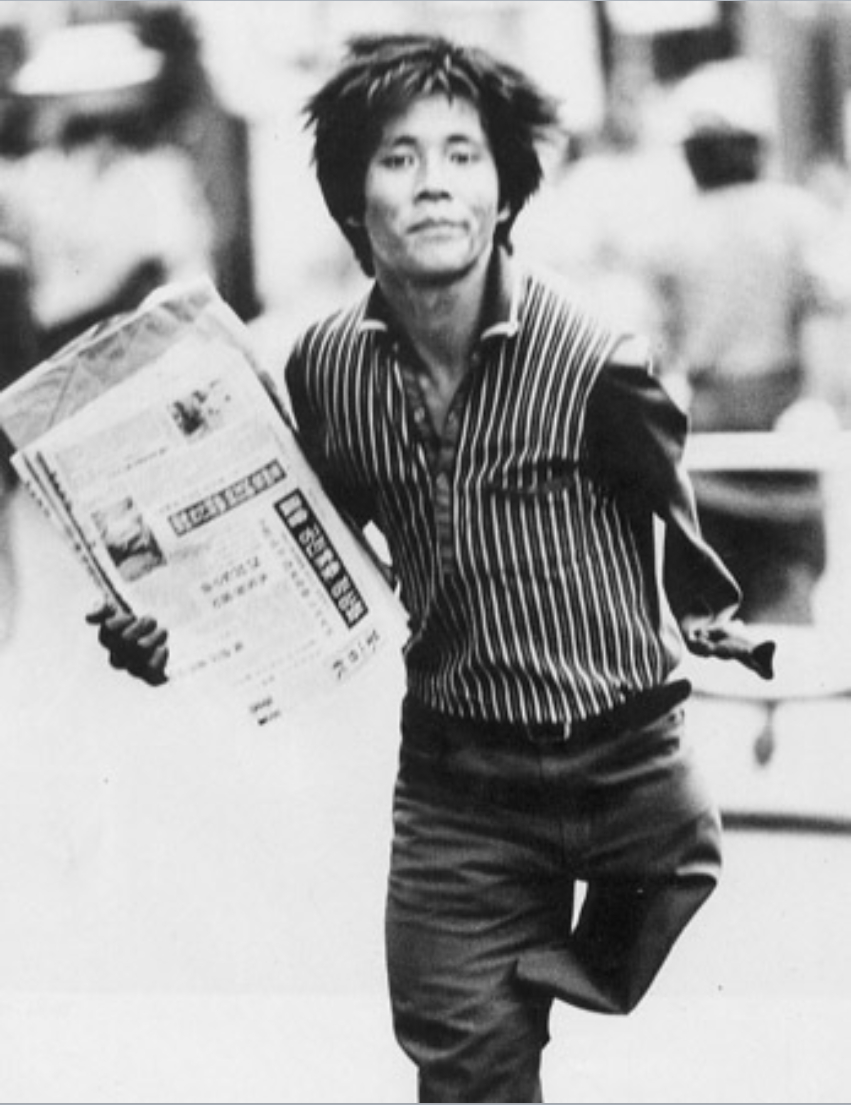

Much to my surprise, I have become known as a street fashion photographer. In my academic work, i have mixed in my photography to call myself a “visual sociologist.” Even though I do a lot of “street fashion photography,” I don not consider myself a fashion person because I am actually not interested in clothing as fashion objects. I am more interested in clothing as wearable cultural texts that are important because clothing, taken as wearable cultural texts, is quite a special thing, a category worthy of special consideration.

Clothing is special in that it is inherently personal in how the wearer makes an active choice to participate in a public, semiotic conversation in which fashion items not only have cultural meaning, but the items themselves are chosen as part of a statement that says something about the wearer. Fashion items are individual objects possessed of various meanings that have been societally assigned to them, much like words within a language, with the wearer choosing to construct these various objects into a greater whole, much like a speaker constructs words s/he learned elsewhere into a sentence. There are grammatical rules that govern the sentences we make, such that they are understandable to other speakers of the language, but we are free to make the statements we want. We can play with the rules, make puns, construct poems, or even choose to obfuscate meaning for rhetorical purposes. And there are myriad styles of speech, some formal, some filled with slang, and some that even purposely violate grammar and usage rules so as to make a certain kind of point. But inevitably, we tend to know what the speaker is trying to say, even if it is unconventional or even sometimes difficult to decipher. And it is sometimes in the violation of these rules, or their reworking or purposeful misapplication, that the fun in language lies.

What can street fashion photography tell us about Korean culture? And totake this line of thinking even further, what is even particularly Korean about Korean street fashion, if it's not all particularly Korean material, patterns, or even brand that we are looking at? Does this mean the only true Korean fashion is the traditional hanbok? What is Korean fashion, really? This is the crux of the existential problem with street fashion of any kind, especially if we are looking at fashion as a window towards understanding culture.

I found this young woman, Gyu-eun, a 3rd-year high school student presently in the final stretch of preparing for the all-important Korean college entrance exam coming up this November 17th, of particular interest this past Seoul Fashion Week (SS 2016) mostly because of her inversion of a basic piece of fashion grammar by her wearing of her shirt backwards. It is a surprising choice, and technically "wrong" (bad fashion grammar), but it works quite well and naturally to the point that I did not consciously notice the choice until I had already decided to start shooting her. Subconsciously, I may have noticed something peculiar, as it may have caused my initial interest in her look, but it was not a conscious reason I chose to photograph her. Her goal of appearing fashionable and unique (despite her having gotten the idea from the fashion pop icon Kim Na Young) was accomplished, but with "bad" fashion grammar. Still, it succinctly and successfully conveys the point, and with a great deal of eloquence that cannot be conveyed with mainstream, "proper" grammar.

Fashion is sociology-in-motion, is a sartorial text worn and displayed on the body, and is more than just a mode of consumption, but is a social conversation that is even possessed of a discernible grammar. In any case, it is certainly indicative of social change, and especially in Korea's case, a marker of how definitions of gender and the modes of its performance are shifting, how basic social norms are metamorphasizing faster than many people can make sense of. And it is through street fashion photography -- the visual medium -- that one can track the actual markers of these changes in a concrete, presentable way, as raw visual data.

Therefore, our project looks at Korean street fashion primarily through the lens of sociology and takes up closely looking at Korean fashion not out of any interest in the pieces of cloth themselves, their branding, prices, or their sale, but rather out of interest in considering their importance as social texts, as ways of knowing how identity is constituted, communicated, and consumed, and how this changing discourse marks significant patterns of social and cultural change.

In short, I am interested in fashion objects as part of a greater discourse, a greater social conversation. And in this way, we see the official event of Seoul Fashion Week as important now because of its accidental role in the formation of what we see as far more culturally important: a social institution centered around fashion, what I like to call “Seoul Street Fashion Week.” In fact, my main reason for regularly covering SFW these days is to cover the street fashion. And I am not the only one. The movers and shakers in this sartorial community are of tantamount importance now, of greater interest to the overseas fashion press than the shows themselves, as recent stories filed about Korean fashionin both the NYT and Vogue USA (both of which completely ignored the runway shows) demonstrate. They’re concerned with the Korean paepi.

In short, the new Korean paepi (패션피플=패피=Korean for "fashion people" or its shortening pae +pi) are engaged in a creative remixing of sartorial grammar on both the individual and group levels. In this sense, they are being quite creative as they express their individuality in a social space that has been long regulated by not just other members of society, but by even the state itself. The sartorial realm has become both a site of identity assertion and contestation for paepi youth, complicated yet even more by the consumptive and commercial nature of fashion as a social endeavour.

Their power isn't in each one being the best dresser ever, or being completely original, but in the act of dressing up itself, in the choice to create a new identity related to the consumption and wearing of clothing. From this culture of consumption, they've created a new class of creative consumption, of asserting identity through clothing in a way new to Korean society.

In this sense, the creative act here Like a 1930's jazz musician in a club, or a early 1980's rapper performing at a local block party, it's not just what they're performing, but the social bravery in the performance that sets the paepi apart, that gives the creative act of riffing or remixing meaning. This is the source of a new kind of creativity in Korean society, a real part of a “creative economy” that is completely missed in the idea that creativity can only be found in traditional institutions and hierarchies such as large jaebeol or large, well-funded professional organizations. The next part of the “Korean Wave” will be found in organic, underground cultures such as the so-called “paepi” as opposed to the runway, in dark, dirty, underground hip hop clubs playing “trap music” as opposed to the military-like training regimes of entertainment conglomerates, and in street food stalls that only take cash within a shadow economy, as opposed to the official food campaigns of large companies trying to package Korean food like western fast food franchises. This is not the culture that will sell overseas; in the new Youtube-enabled, reality TV-influenced media culture, people want the Real. They want authenticity. Culture packaged in plastic isn’t going to go far in the future. We need to look at the cultures of the street right in front of our eyes.