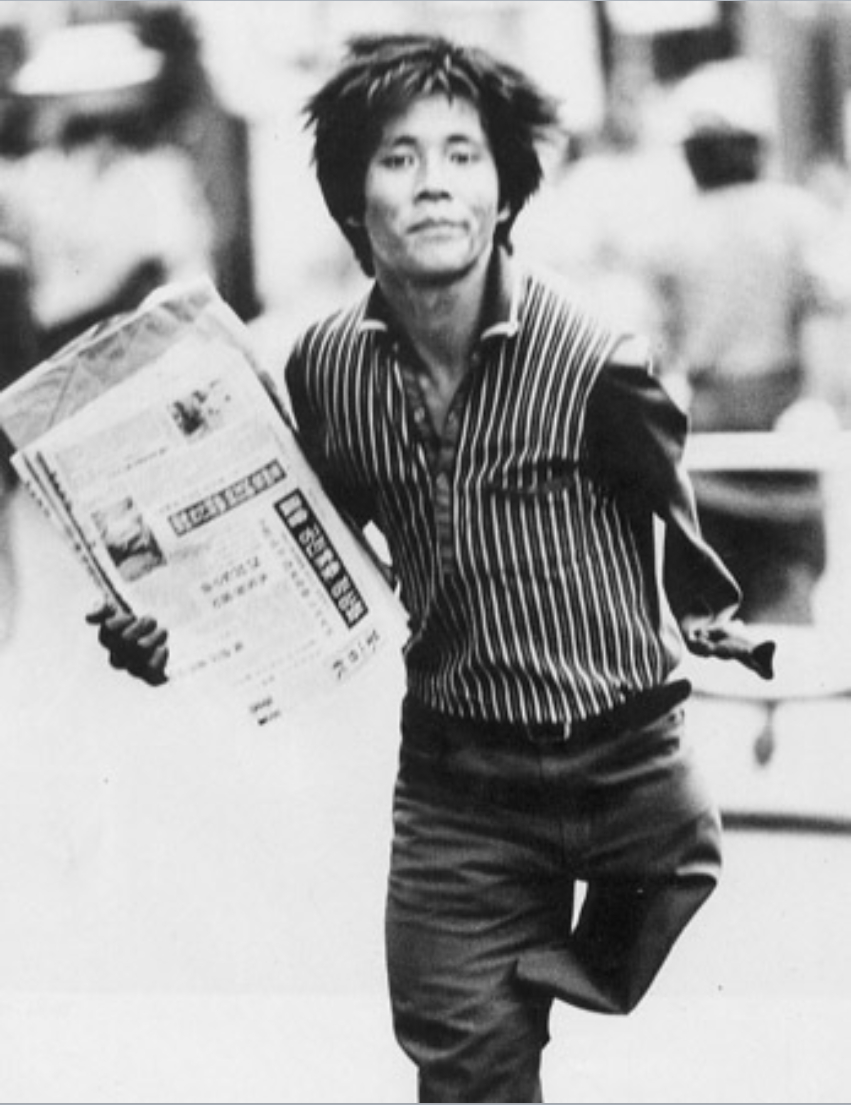

Dr. hurt’s students in the field.

The world has recently been surprised at how quickly and successfully Korea has “gone global.” In terms of popular culture success, South Korea has become the world’s new wunderkind. Fom PSY to Bong Joon-Ho, Korean popular culture has been commanding the world’s attention, and no field has been more successful than K-POP, which has rebranded Korea’s image into one of an undaunted, effortless cool. This class continues an empirical, ethnographic investigation into the way a Korean style defines the snowballing interest in Korean popular culture that is quickly spreading across the planet. This course makes the argument that there is a Korean style (beyond just clothing) that allows the various parts of what people call the "Korean wave" or hallyu to actually cohere as a singular phenomenon. That style is an interstitial fluid that gives coherence to all the parts, allows one part to communicate with others, and can be seen in society as a complex and densely interwoven skein of Koreanness that makes a greater, larger whole that has tendrils digitally spreading across the earth . We posit that Korean popular culture has a mode and form that defines a a clear Korean style. Our exploration of clothing, space, and consumer identity will help us more clearly define the features of this Korean style. It's certainly there in clothing since Korean style is all the rage in Vietnam, China and most other places in Asia. The styles apparent in the worn items of fashion (clothing) are only the obvious manifestation of a larger Korean style, one that echoes in the music, cinema, television dramas, and of course, actual fashion.

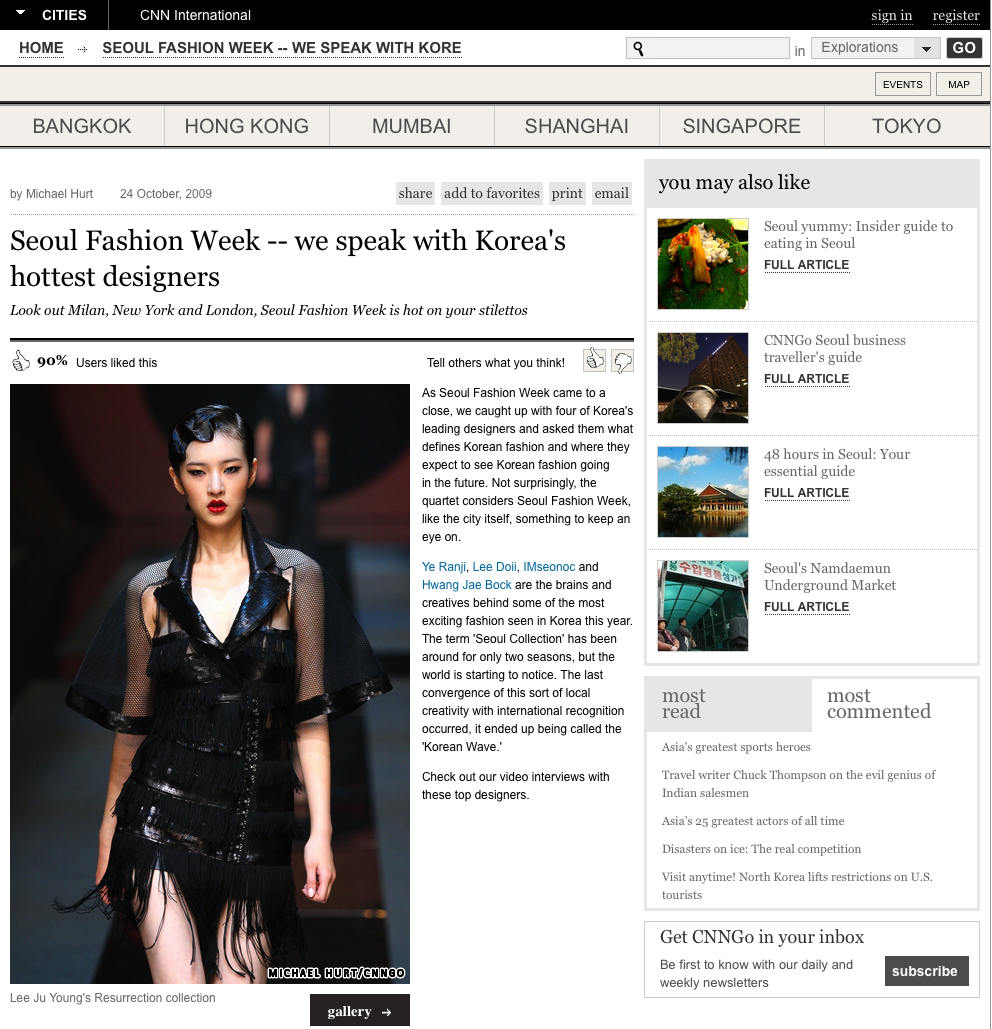

There is a world before Beyoncé wore a Korean shirtdress from GREEDILOUS to sister Solange’s concert in 2017, and then there is the world after. The tendrils of a Korean style now reach across the planet quite concretely, and the mode of fashion is only one of its means of propagation.

This fieldwork unit will place the student into an all-too-rare, real experience with academic praxis that unites theory with practice to produce a d peeper kind of knowledge and learning experience. In this learning unit, the student will be given a deep, theoretical introduction to the theory that will focus the empirical, on-the-street research into defining a Korean style. The course will have students attempt to answer — through social data-gathering — this larger question of how Korean style gets defined globally, along with the question of whether globality itself is the central element of Korean style.

Salim, one of Vietnam’s most influential fashionistas, with 880K followers on Instagram (@salimhwg) wears a dress by top Korean brand GREEDILOUS in Hanoi, 2018. Vietnam holds one of the most positive images of Korean style in the world.PHOTO by Dr. Michael W. Hurt

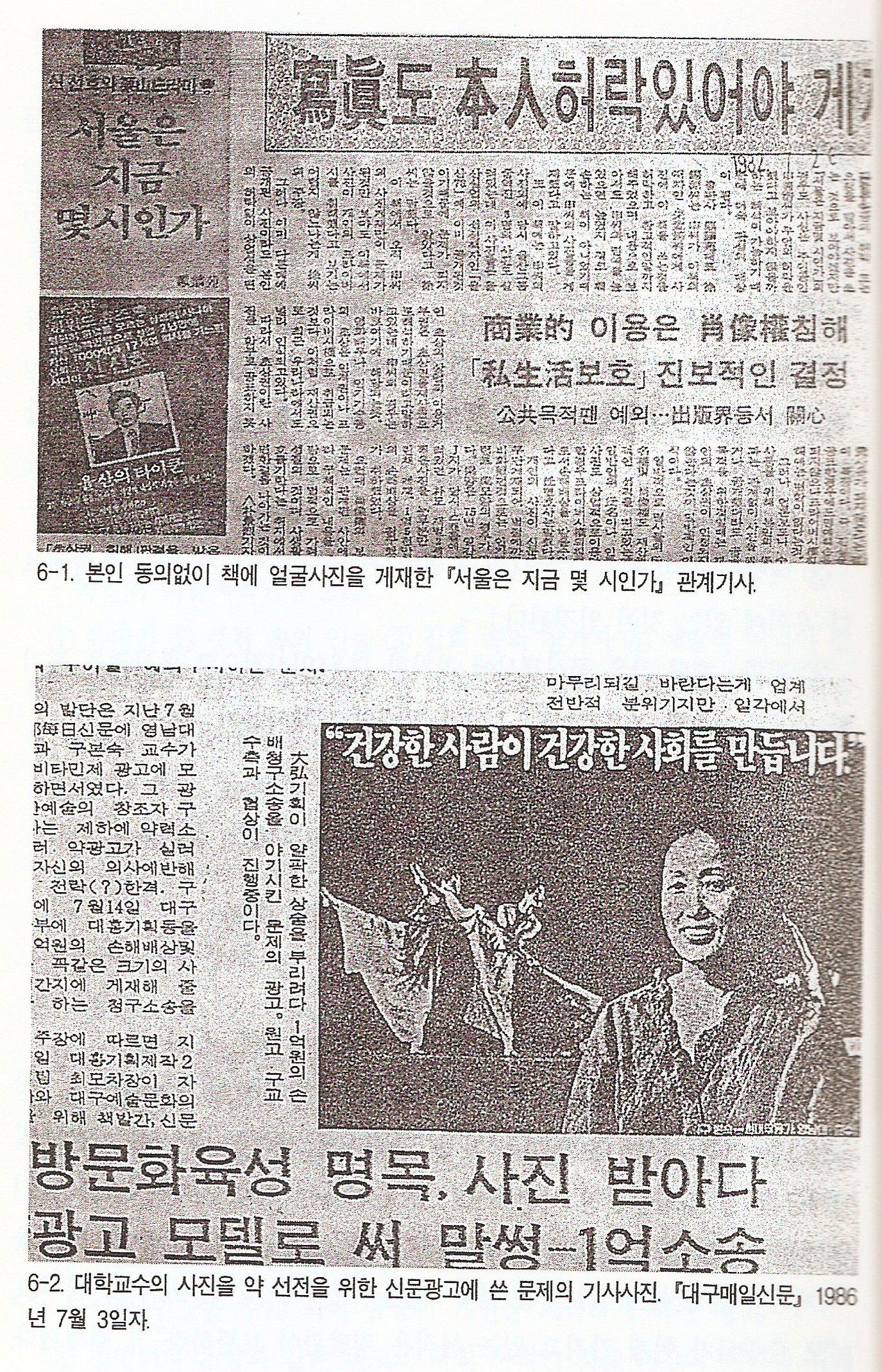

Dr. Hurt’s notes on a standing wave theory of style transmission.

COURSE SCHEDULE

THEORY (Weeks 1-2)

Combined with about two weeks of theoretical prep with Dr. Hurt, there will be a technical primer that will teach you how to use a DSLR and the basics of photographic theory, from ISO to the aperture-shutter speed-depth-of-field. relationship. Additionally, intern/mentees will learn the basics of doing ethnographic work in the field with an audio recorder (nowadays, a built-in capability of the hand computer/”smartphone.” Then the student will be ready for contact in the field at Seoul Fashion Week.

PRAKTIKUM (Week 3

The Seoul Fashion Week (hereafter, SFW) event will require the integration of all knowledge and skills learned to that point in the class as students participate in everything from schlepping gear to catching interview/photo subjects, and other myriad activities at the DDP site.

Dr. Hurt on site at DDP, in the field.

WRITE-UP (Week 4)

Since data is worthless without parsing and publishing it, the final week will be spent on getting it out into the light of day. This will take up the form of some integrated presentation of text, image, video, and sound. Although publication types will vary according to students and needs, some integration of the data as already collated as images on Instagram, audio in Soundcloud, and video on YouTube will be united into a text/research/source-based essay, which will be published in a place such as Medium or some other social media publishing platform. All projects will be summed up in a public presentation in a conference format.

An academic presentation with PPT and an audience is a standard way to present research findings.

There are many ways to present social information. One of them can be as a fashion lookbook in a local textile newspaper.

lWhen Dr. Hurt interviewed Paris Hilton in Seol for WWD, she arrive to the press event in a GREEDILOUS dress.

PHOTOby Dr. Michael W. Hurt

COURSE RESULTS

POSSIBLE CONCRETE DELIVERABLES

Ethnographic interviews as shareable SoundCloud files

YouTube-based video interviews

Portfolio of photographs published in a dedicated Instagram feed.

SKILLS GAINED

confidence gained from conducting live, impromptu interviews

producing creative output under pressure

constructive, creative use of social media for professional application

constructing research plans

project management skills

INTEGRATED RESEARCH RESULTS OUTPUT

a multimedia research paper writeup (8,000 words) that both shows the data directly and tells its story (through Medium)

Publishing the data through a data write-up creatively through Instagram/Instagram Stories

a YouTube video presentation of the data

![By Eugene Lim [CC BY 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56e92599a3360ca7c0e2b668/1491569695484-GSR49M70QEKK2X4K0GCX/image-asset.jpeg)

![The entire image, uncropped. [Source] ](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56e92599a3360ca7c0e2b668/1460719831791-CCL78O0FGCR2NDC9TD8T/image-asset.jpeg)